Women and Bone Density

What is bone density and why does it matter?

Fractures in post-menopausal women are a significant problem in Australia. Research shows that 1 in 2 women over 60 will sustain a hip fracture in their lifetime (Australian Menopause Society, 2019). Poor bone health and increased falls risk are two major fracture risk factors. To reduce the impact of fractures on the community, interventions should look to improve bone health as well as reduce falls risk.

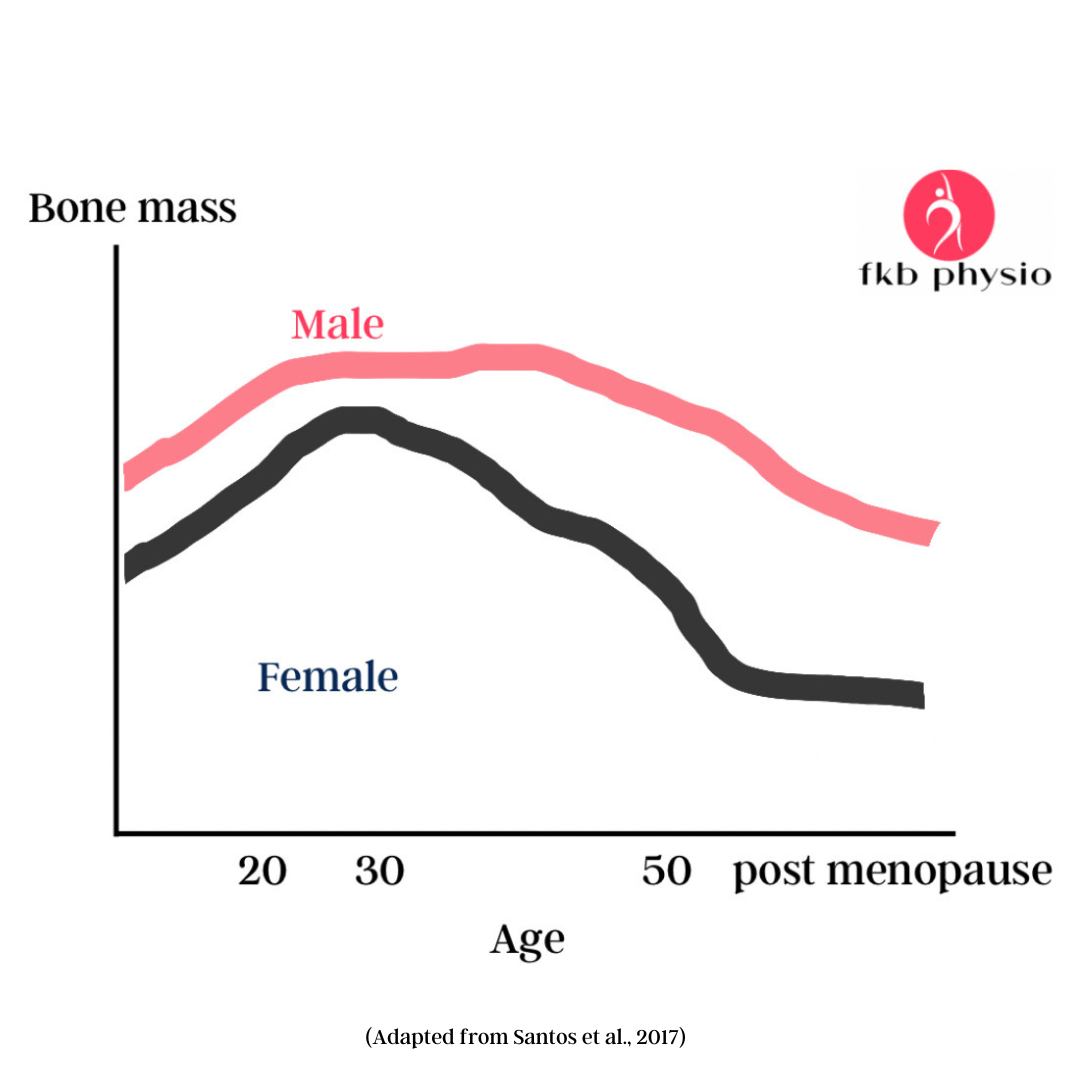

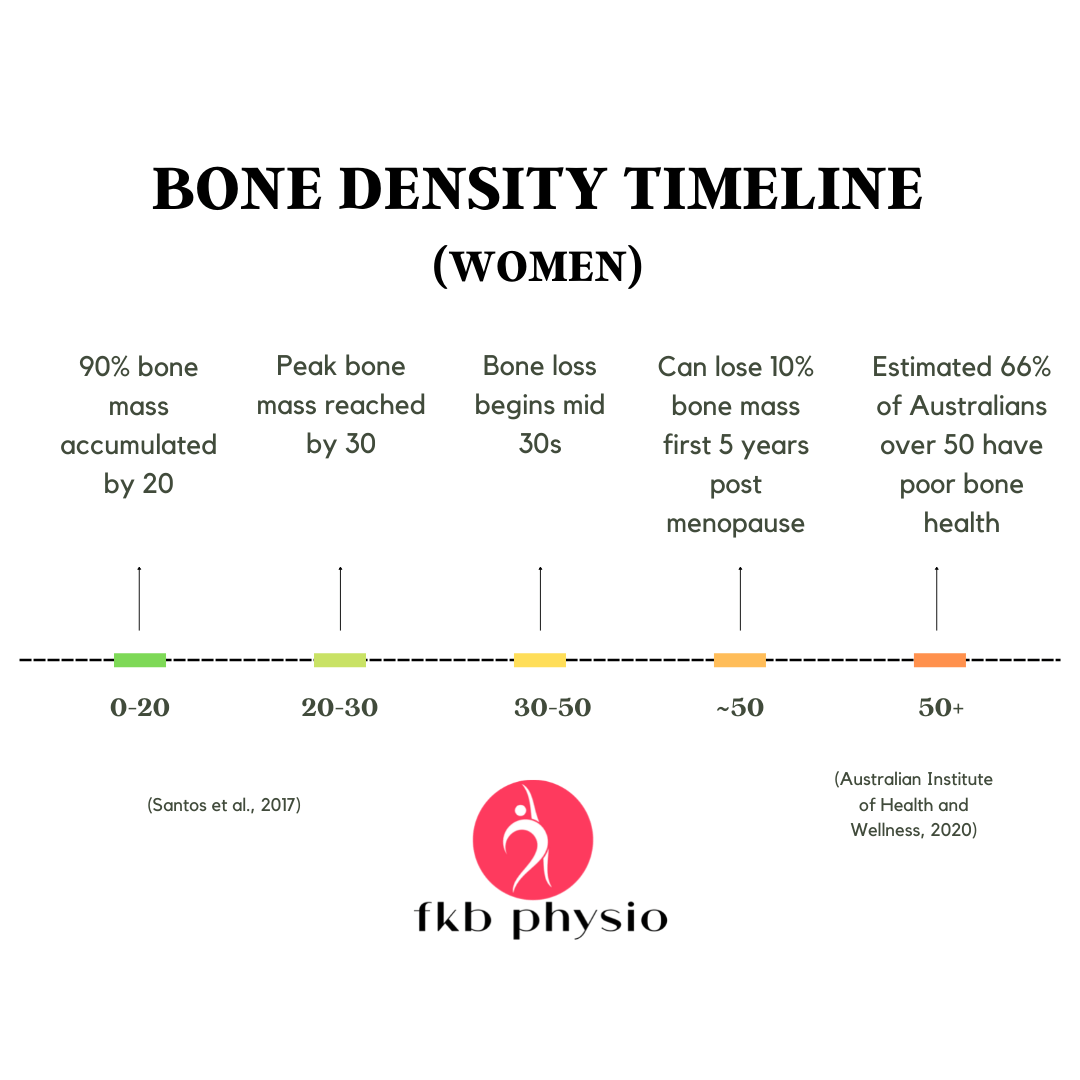

Bone density increases until approximately mid 30s (Tu et al., 2018). It is thought that having a 10% higher peak bone mass (building your bones as much as possible!) can delay the onset of osteoporosis by 13 years (Santos et al., 2017).

In 2012, Osteoporosis Australia estimated that 66% of all Australians over 50 had poor bone health, with women impacted more significantly than men (Australian Institute of Health and Wellness, 2020). Fractures can often occur prior to an osteoporosis diagnosis, and sometimes a fracture is the first indicator that one has the condition (Daly et al., 2020). This presents a challenge, as many interventions designed to reduce fracture risk are available only to those with a diagnosis.

How can physiotherapy help?

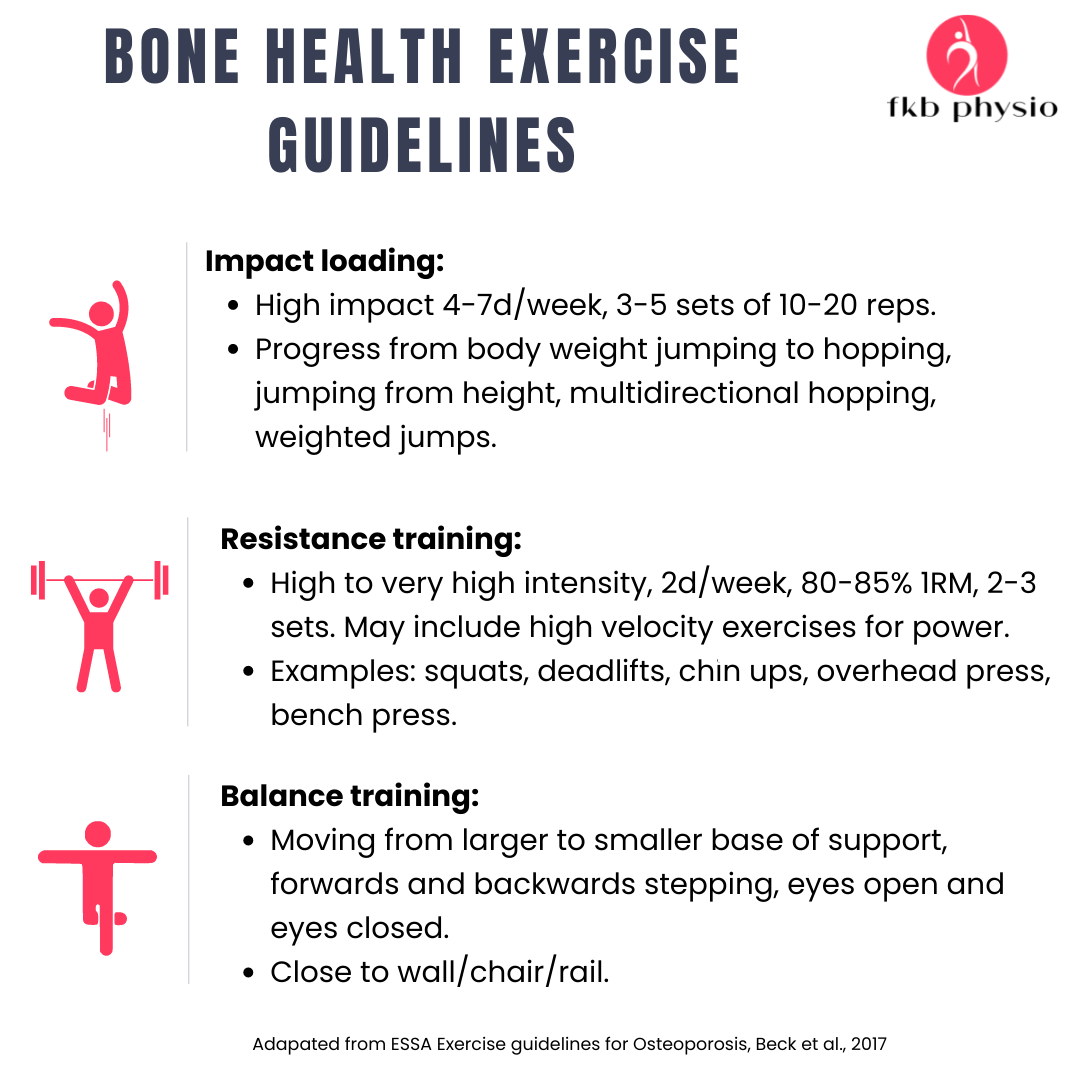

Physiotherapy’s role in fracture risk reduction in women over 50 primarily involves exercise-based interventions which target bone health as well as reduce the risk of falls. Beck et al. (2017) present evidence-based guidelines for exercise in the management and prevention of osteoporosis:

Previously, high impact (i.e. jumping) and high intensity (i.e. heavy lifting) exercises were avoided in older adults and particularly those with osteoporosis due to the assumed risk of fracture it posed, however there have been no adverse events noted in recent studies using this type of exercise in participants with osteoporosis (Daly et al., 2020; Watson et al., 2017). Belinda Beck has also written a paper this year in 2022 reporting her in-clinic experience running the bone clinic since 2015 and has reported no adverse events across those 7 years.

What research supports these guidelines?

Watson et al. (2018) investigated supervised high intensity and high impact resistance training in patients with osteoporosis and the impact on BMD. Training was performed twice per week for a period of 8 months. This is the LIFTMOR trial, the program of which is run at the bone clinic. The high intensity group experienced improvements in bone density in the lumbar spine compared to controls who used 3kg weights at home, though these increases were modest, ranging from 0.3-2.9%. While there was no improvement of BMD at the femoral neck, there was a significant improvement in cortical thickness.

Daly et al. (2020) performed an 18 month trial of a multi-modal program including strength training as well as balance exercises. Results demonstrated an improvement of BMD at the lumbar spine and hip by 1%, but no reduction in falls, though a net benefit of exercise in terms of muscle strength and overall function was noted.

These are just two of many studies published in the last 10 years investigating the impact of exercise on bone health and falls risk. When looking at the influence of exercise on BMD, while results are often fairly modest, this statistic alone does not tell the full story. It is thought that bone density (the reading you will get on a deja scan) accounts for only 60% of the actual profile of bone fragility as it cannot measure changes in bone structure (Osterhoff et al., 2016).

The other point to consider is how beneficial exercise is in other ways. Not only can it improve bone health, but may also improve muscle mass, balance, power, cardiac fitness, body composition, confidence, and mental well-being. Less than 25% of adults meet the WHO recommended exercise guidelines for resistance training, which is recommended twice per week.

How can classes in particular be beneficial?

It can be challenging to encourage older adults to exercise in a gym. A group, as well as supervision by a physiotherapist, increases safety, reduces the cost and provides social support (Burton et al., 2017).

Another positive of group classes is the motivation the members gain from working with each other, and seeing other people similar to themselves pushing themselves to lift heavier or to try an exercise they have previously been fearful of. I see this time and time again in my classes.

Why can’t I just take the bone density medications instead?

While pharmaceutical interventions to improve bone density can reduce risk of fracture, they do not reduce risk of falls, and do not target other concerns for post-menopausal women such as reduced muscle strength and size (Daly et al., 2019). Additionally, pharmaceutical interventions require a diagnosis of osteoporosis. Bone density classes can improve bone health in women without requiring this diagnosis. (But you should liase with your GP about whether you need these.)

How often should people be participating in the class?

Research shows resistance training must be completed on an ongoing basis and a minimum of twice per week to be effective (Beck et al., 2017).

What are the costs and how is it set up?

The classes are one physio to 3-4 people. Cost is $40 per person and can be rebated on private health. Those wishing to attend a class are initially required to attend an initial assessment, in which we go through a past medical history, a physical assessment, and a discussion of goals. A program is devised according to this assessment and tailored to the individual.

In my classes, I create a 3 day rotating program, that usually starts with large compound exercises (bit movements that use lots of muscles ) first, and then moves to single joint exercises (smaller exercises working one area at a time), finishing with impact loading, core and balance work. Once each day of the program has been completed four times, I change to a new program.

Over time, people are progressed as they improve.

For example, a woman who has never done gym based exercise in her life time might begin with body weight squats, 5kg deadlifts, 3 sets of 10 light jumps holding a rail, and 2kg upper body weights. In 6 months, she may be up to 20kg deadlifts, 3-5kgs upper body weights, and 5 sets of 10 heavier jumping. At one year, she may be up to a 35kg deadlift using the hexagonal bar, bench pressing 20kgs, overhead pressing 10kgs, and performing 6 sets of 10 jumps holding a weight.

A final benefit of the class is that whenever a musculoskeletal problem crops up, as inevitably does, we can monitor and manage it during the classes. My clients who have had hip or knee replacements have been able to attend right up until their surgeries and come back afterwards, enabling weekly or twice weekly monitoring of their progress. If someone wakes up with a sore neck or lower back, we are able to change the class around the issue until it resolves, while monitoring the need for any additional care. This continuity of care and follow up over a prolonged period to me is really what healthcare should be all about.

References

1. Australian Menopause Society, https://www.menopause.org.au/.

3. Beck, B. R., Daly, R. M., Singh, M. A., & Taaffe, D. R. (2017). Exercise and Sports Science Australia (ESSA) position statement on exercise prescription for the prevention and management of osteoporosis. J Sci Med Sport, 20(5), 438-445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2016.10.001

4. Beck, B. R. (2022). Exercise Prescription for Osteoporosis: Back to Basics. Exerc Sport Sci Rev, 50(2), 57-64. https://doi.org/10.1249/jes.0000000000000281

5. Burton, E., Farrier, K., Lewin, G., Pettigrew, S., Hill, A. M., Airey, P., Bainbridge, L., &

7. Daly, R. M., Dalla Via, J., Duckham, R. L., Fraser, S. F., & Helge, E. W. (2019). Exercise for the prevention of osteoporosis in postmenopausal women: an evidence-based guide to the optimal prescription. Braz J Phys Ther, 23(2), 170-180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjpt.2018.11.011

8. Daly, R. M., Gianoudis, J., Kersh, M. E., Bailey, C. A., Ebeling, P. R., Krug, R., Nowson,

9. C. A., Hill, K., & Sanders, K. M. (2020). Effects of a 12-Month Supervised, Community-Based, Multimodal Exercise Program Followed by a 6-Month Research-to-Practice Transition on Bone Mineral Density, Trabecular Microarchitecture, and Physical Function in Older Adults: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Bone Miner Res, 35(3), 419-429. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3865

10. Osterhoff, G., Morgan, E. F., Shefelbine, S. J., Karim, L., McNamara, L. M., & Augat, P. (2016). Bone mechanical properties and changes with osteoporosis. Injury, 47 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), S11-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0020-1383(16)47003-8

11. Santos L, Elliott-Sale KJ, Sale C. Exercise and bone health across the lifespan. Biogerontology. 2017 Dec;18(6):931-946. doi: 10.1007/ s10522-017-9732-6. Epub 2017 Oct 20. PMID: 29052784; PMCID: PMC5684300.

- Watson, S. L., Weeks, B. K., Weis, L. J., Harding, A. T., Horan, S. A., & Beck, B. R. (2018). High-Intensity Resistance and Impact Training Improves Bone Mineral Density and Physical Function in Postmenopausal Women With Osteopenia and Osteoporosis: The LIFTMOR Randomized Controlled Trial. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, 33(2), 211-220. https://doi.org/10.1002/jbmr.3284